If you are under the impression that target shooting requires eyesight, I am here to prove you wrong. It’s nothing personal, but rather a passion of mine. We all fall into the trap of believing that something must be done how it has always been done. In reality, looking through a rifle scope is the easiest part of precision shooting.

The Desire

I grew up learning about firearms, hunting, and military service. It may seem strange to people with a different background, but I believe this environment developed my sense of ethics, drive, humility, and gratitude for the sacrifices of others. Hunters should be grateful for the food they can provide their loved ones while understanding they have a duty to minimize the animal’s suffering. Hearing the stories of my grandfather and uncles in World War II provided me with so much perspective on what it means to give yourself to a higher cause. Rather than become a “gun fanatic” as some fear, I have a deep admiration for those who use firearms to provide and protect.

Being diagnosed with vision loss when I was 3 years old and declared totally blind in my teens made shooting sports difficult. I attempted to use the small amount of vision in my right eye by adding contrast to targets and the gun sights. This never really worked, of course. Nevertheless, my fond memories of shooting pellet guns at our family cabin are part of the inspiration for what I do now. Friends and family are well aware that I can be independent to a fault. Having someone look over my shoulder to help aim might have allowed me to hit the target, but it certainly didn’t satisfy me.

Setting the Goal

Over the years I lost my remaining vision. On the other hand, my interest in precision target shooting only grew. Any book or movie about the incredible skills of military snipers is a must for me. As I said above, shooting is only partly visual. A shooter must understand the physics of bullet flight; a shooter must interpret and account for the environment around them; and, perhaps most importantly, a truly excellent shooter has learned mental and physical control. These are the skills I wish to develop and use. Why should blindness be a barrier to that?

The highlight of my high school years was physics. Mr. Green took on the challenge of a blind student like nobody else. I was never “along for the ride” in that classroom. A surprisingly relevant example comes from learning light diffraction. In this experiment, we shined differently colored lasers at the wall through small comb-like slits. This produces dots on the wall to the left and right of where the laser was aimed. Students had to measure how far these dots were from center to determine the angle of diffraction. The obvious answer was to put me in a group and have the other students take the measurements and dictate them to me. After all, I would still do the math and understand the concept.

That just wasn’t how Mr. Green saw things. He knew that doing always teaches more than watching or listening. So, he thought ahead and mounted a digital light sensor to a track against a wall at the front of the room. I could then connect this sensor to my computer and hear light intensity readings in realtime. Once a friend and I powered on a laser, we slid the light sensor along the track until the sensor suddenly spiked where the diffracted beam of light hit it. This took time and effort to assemble and put away after class. It may seem simple and almost unnecessary, but this perfectly demonstrates finding alternate methods for perceiving information.

I discovered software engineering while studying at Stanford University. It didn’t take long before I began to envision leveraging my new skills to bring an old dream to fruition. I never set out to build an “aiming system” at all. Somehow it needed to tell me how far up/down and left/right my sights were from the target. I quickly established a challenging set of parameters for the project.

- The system should not provide any advantages to a blind shooter. I want to learn and develop the same shooting techniques as any sighted shooter.

- A blind shooter should not be limited to particular firearms, optics, or other hardware. In short, I certainly did not want to build a gun myself.

- Minimize building custom hardware. Hoping to keep the system to a reasonable price, I wanted to use primarily off-the-shelf components.

- Every effort must be taken to build a safe shooting experience. It is crucial that every shooter be aware of range commands at all times and that none of the equipment pose any hazard to moving around the shooting line.

- And, of course, it better be accurate! Most people doubted me on this point. I was told many times that precision shooting is hard. I just want a system that allows me to practice.

The Long Game

This project has been a true marathon. I have gone through many design concepts over the years. The core idea formed early: process realtime video through a rifle scope. This processing must detect the target and determine its position relative to the center of the scope’s crosshairs. Somehow the result should be turned into audible information for the shooter.

As confident as I felt that the idea could work, every engineer knows that a project starts with a proof-of-concept. My search for possible starting points ran far and wide. I purchased numerous action cameras to evaluate how they might mount to a scope and whether-or-not they could provide adequate live video. The breakthrough came about 2 years ago when I discovered the Tactacam 5.0 action camera and the Film Through Scope (FTS) mount. Connecting the HDMI output from the camera to my computer, I dove into developing the software. Being far from a computer vision expert, the learning curve was fairly steep. Obviously there aren’t tutorials on this kind of thing.

In typical fashion, I went through countless experiments and iterations before ever reaching a promising demonstration. I designed my own custom targets; I studied computer vision textbooks; and, above all, I drove family and friends crazy looking at video clips. Once an initial algorithm was in working order, the focus moved to audio. Spatial, particularly binaural, audio has been an interest of mine since college. Give the Virtual Barber Shop a listen below if you are not familiar with the concept. A future post will go into greater detail and include audio samples from the working system.

The Moment of Truth

“Fire…”, I called out from behind my new Ruger Precision Rifle. The rifle had not been fired and the scope was only boresighted at the shop. My first shot was taken from 50 yards at the family cabin in Northern California. My shooting bench was an unstable picnic table and my parents watched and waited to see just how far off the target I would be. The target, by the way, was placed where my grandfather sighted in his rifles before hunting season each year. He died before I was born, but I am certain he never would have dreamed his blind grandson would shoot in that same spot. “Bang…”

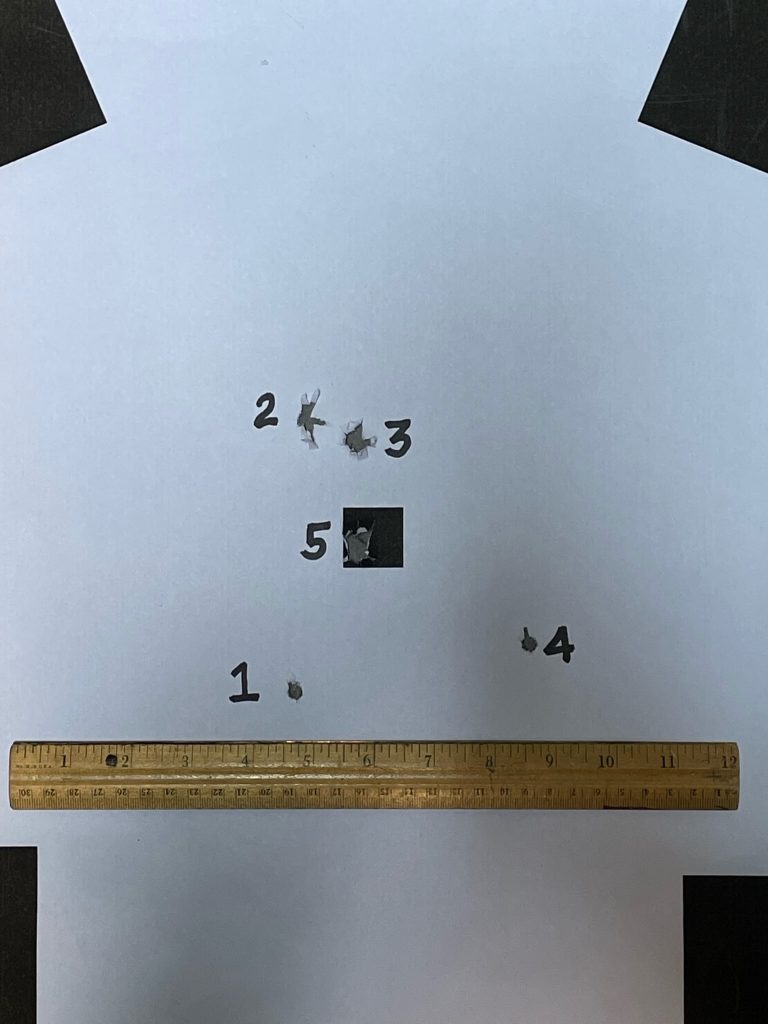

“Honestly, I didn’t expect you to hit the paper… much less 4 inches from the bullseye,” was pretty much the consensus from both of my parents. Don’t take that the wrong way, my parents have been supportive of all of my wild ideas. It does feel good to occasionally surprise even them. I surprised myself on day 2 by successfully sighting in my scope at 85 yards in exactly 5 shots.

It’s Just the Beginning

My SniperSound project has been a blast already. Since those first shots, I have made many enhancements and have already begun developing my shooting technique. All new hardware has made the system smaller, easier to use, and incredibly precise. I am convinced others would find joy, community, and independence on the shooting range. Come back to follow the project’s progress. It certainly is not stopping at 80 yards.